The Discovery and Development of Cerophyl

Cerophyl 1937

The Conception of Ideas and First Trials

Studies published in the early part of the 20th Century had shown that the chlorophyll molecule was very similar to the heme molecule, which makes up red blood cells. In 1927, Charles Schnabel reasoned that green vegetables would build blood and stimulate chickens to produce more eggs.

At the time he started his research, poultry farmers were lucky if 30% of their chickens laid eggs each day. He tried many vegetables including the greens from turnips and mustard and even alfalfa to no success.

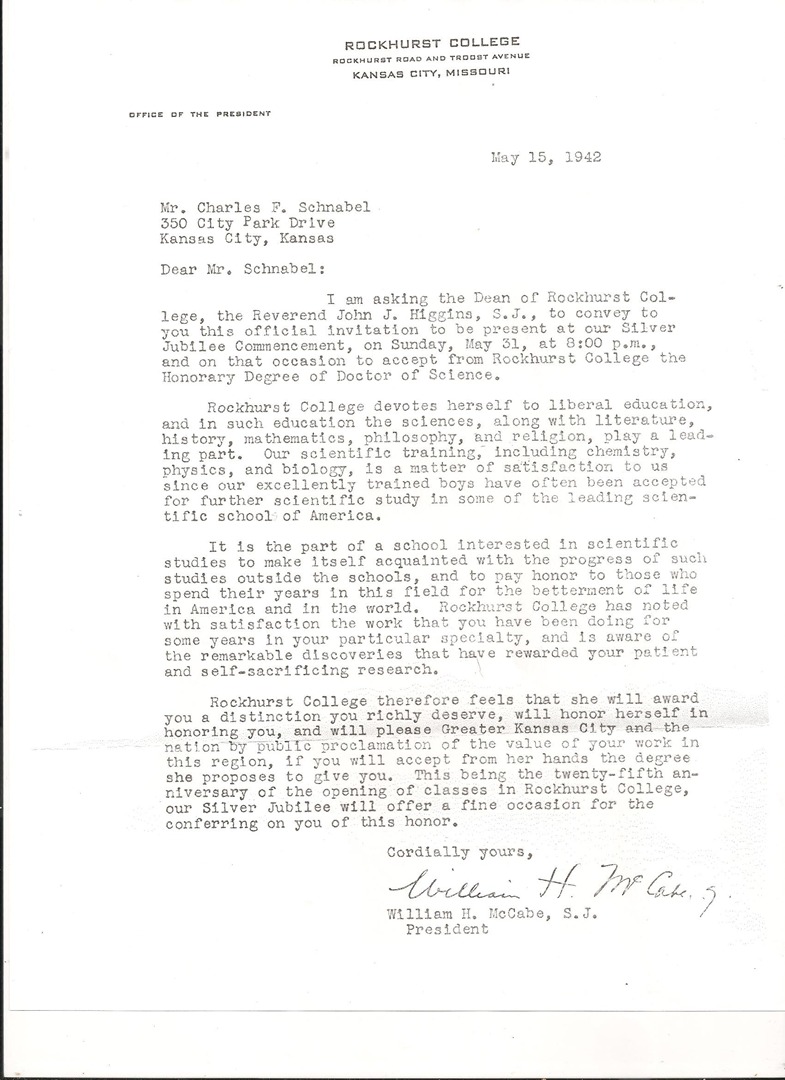

In 1930, Schnabel dried some young cereal grass leaves that were harvested just before the jointing stage. He added a small amount of the grass powder to the food for 106 hens. Suddenly, he started gathering more than 100 eggs each day.

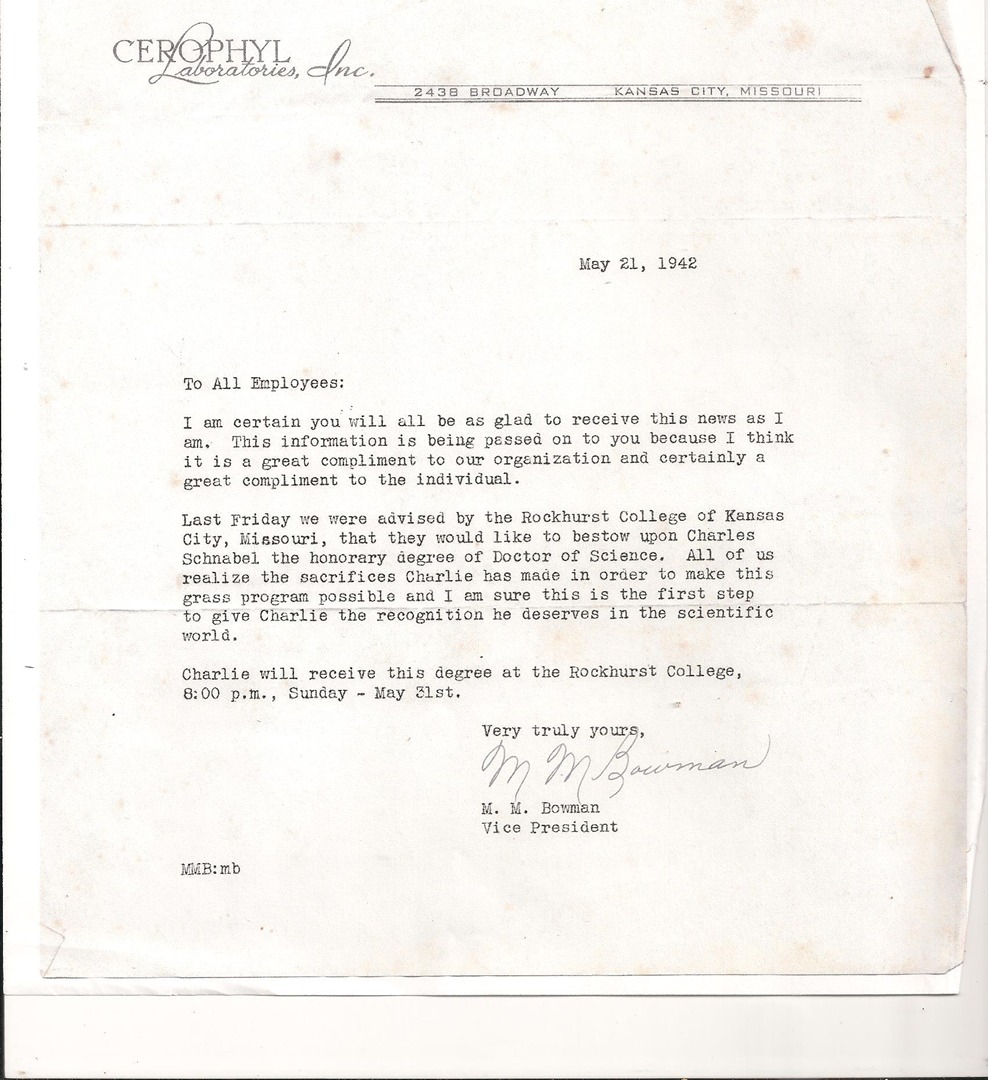

As a millfeed chemist, Schnabel was anxious to try the unjointed cereal grass on other animals, including humans. That is why he established a company that would research these grasses for animal feeds and another one named "Cerophyl" that would supply dehydrated cereal grass tablets and powder for human research.

To keep up with the growing demand, Schnabel established a production facility in Midland, KS, which is just north of Lawrence. He favored the rich glacial soils that are only found in northeastern Kansas.

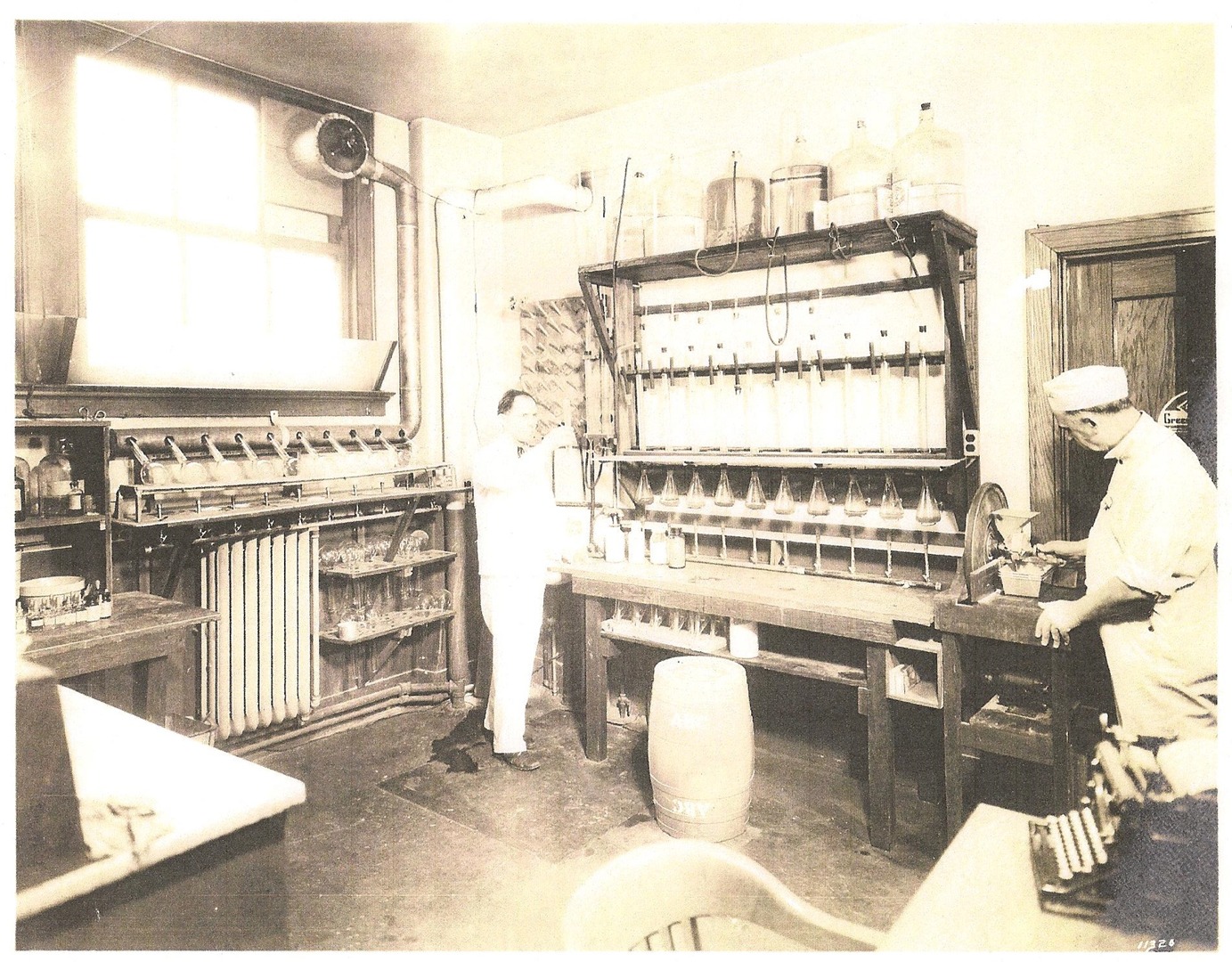

The Midland plant contained an auxiliary laboratory, which fed data to the main Cerophyl laboratory in Kansas City. Pines International continually operates the Midland facility today.

From the start, the data were impressive. Guinea pigs were given small amounts of dried cereal grass in their diets. Just like what happened to the chickens, the supplement produced obvious health improvements for them.

All farm animals benefitted from the blood-building components in the dried powder. They had larger and healthier litters and produced richer milk in larger amounts. All of the animals also showed marked improvement in overall health. Instances of diseases and infections decreased even with only less than 10% of dried cereal grass added to their rations.

Doctors and hospitals were finding similar results when using Cerophyl. Thus, the supplement quickly became the world's first multivitamin before synthetics came on the market. Newspapers and magazines such as Time, Reader's Digest, and Business Week were sharing Schnabel's findings.

Decline and Reintroduction

As synthetic vitamins became more common, the popularity of Cerophyl waned. Then, in 1976, Pines International re-introduced essentially the same product, the Pines Wheat Grass, as a dark green vegetable.

The company manufactures the product using the same standards established by Cerophyl for growing, harvesting, and storing. They also continued to package them in oxygen-free amber glass bottles with special metal caps—similar to those utilized by Cerophyl before. This prevents oxidation and the loss of nutrients.

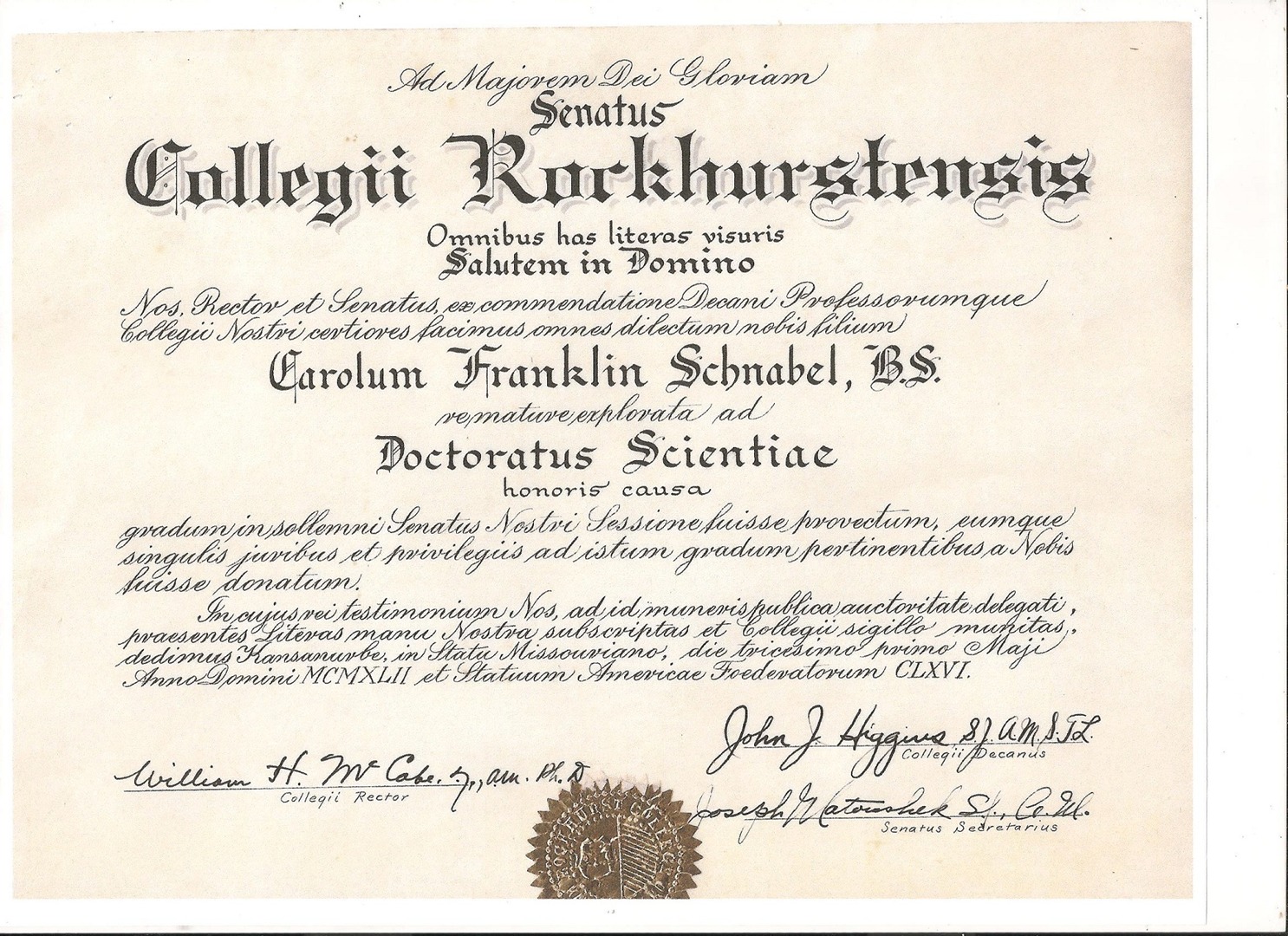

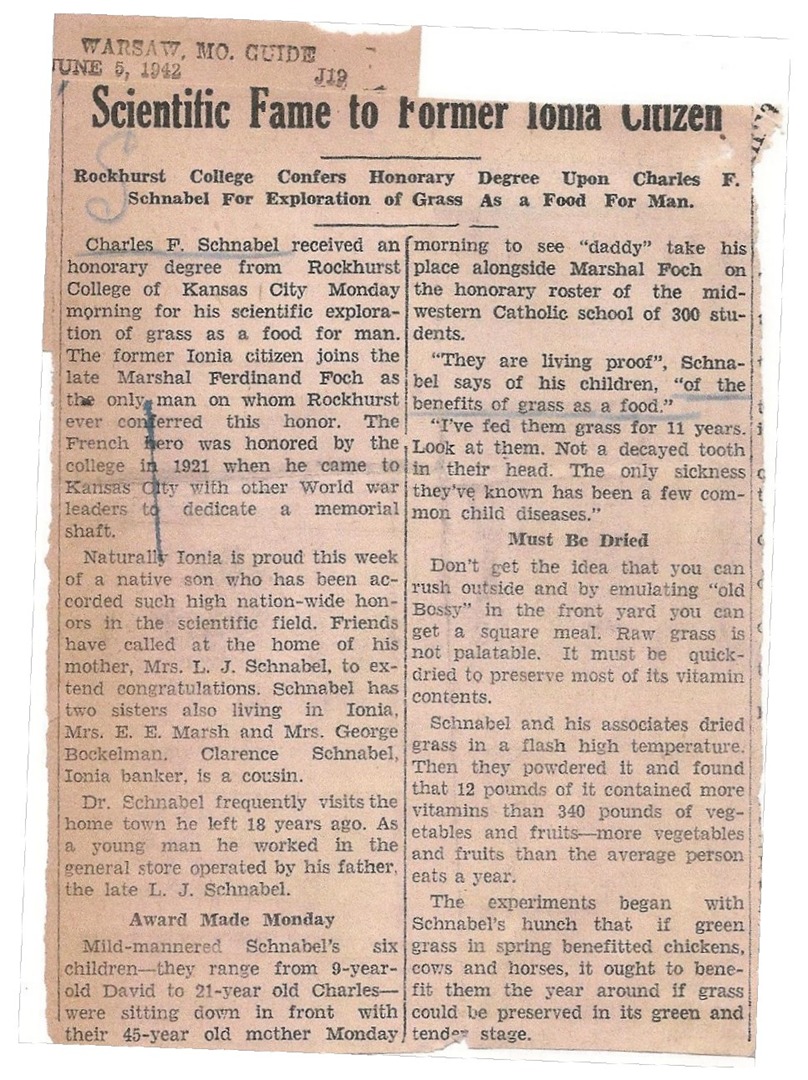

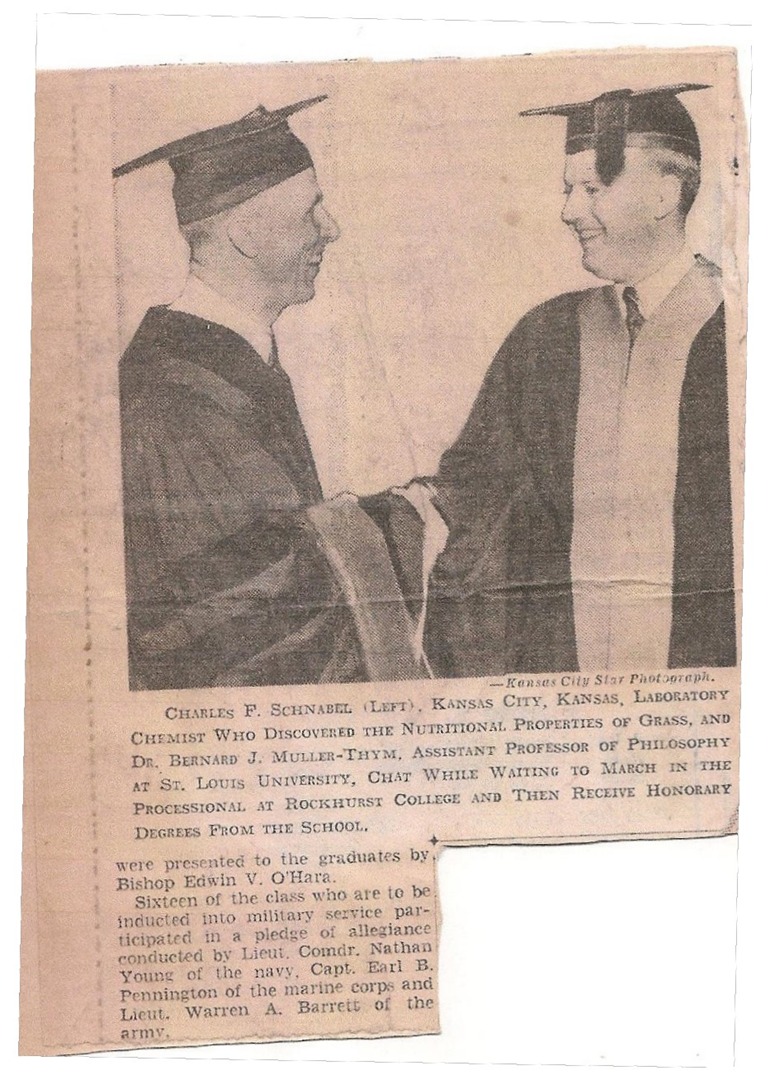

Cerophyl Literature Circa 1942

Schnabel's Bio

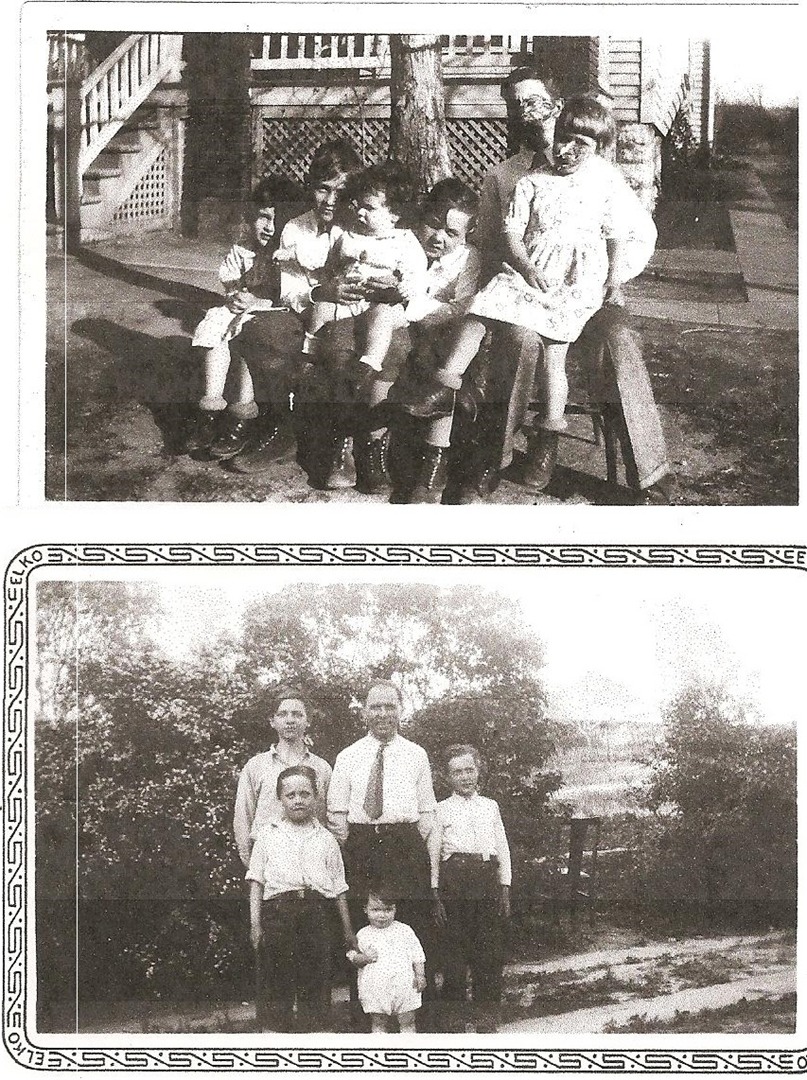

Dr. Schnabel's Family

Charles Schnabel was born and raised in Ionia, MO. He was married and became the father of six children—four boys and two girls. They were raised in the house shown in the pictures below.

Schnabel was married to Julia for more than 50 years. When he died in 1974, he was remembered by his wife, brother, 2 sisters, 6 children, 24 grandchildren, and 12 great-grandchildren.

Early Years

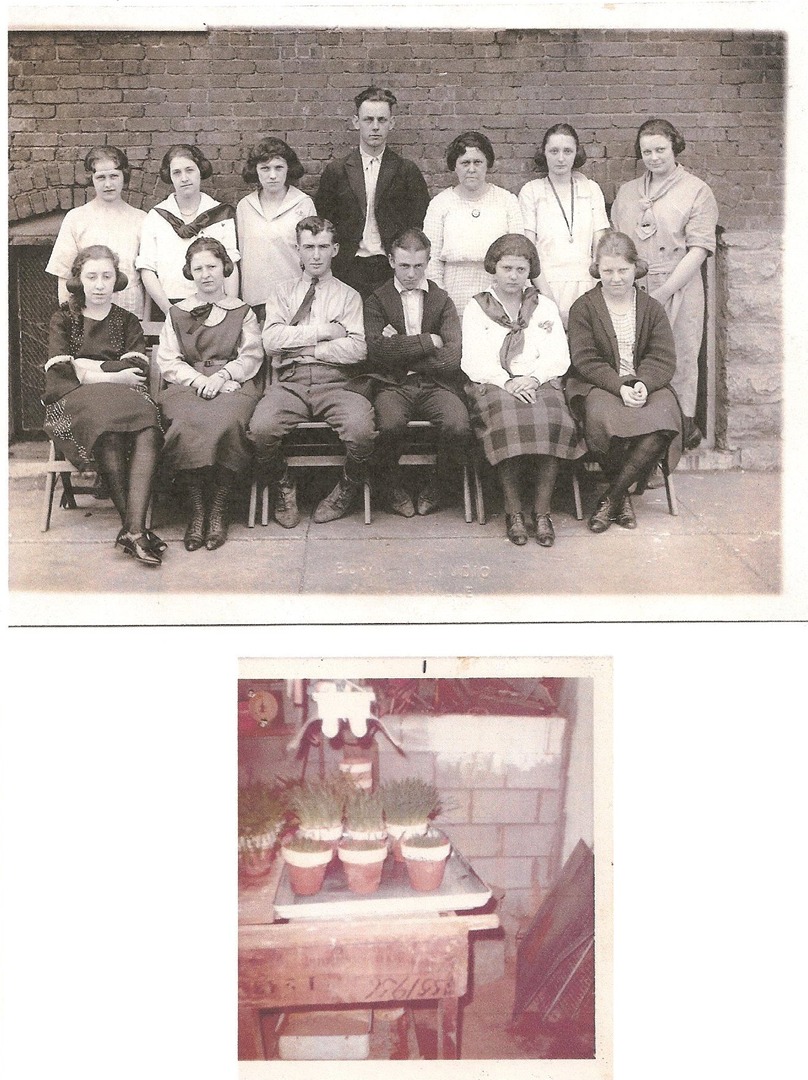

Schnabel graduated from the University of Missouri-Columbia. He taught agricultural science at the Excelsior Springs High School in Missouri. Schnabel became superintendent of schools in Raymore District of Cass County, MO, before moving to Kansas City, KS in the 1920s.

Schnabel had been a self-employed nutritional chemist, but between 1923 to 1933, he was the chief chemist for the state grain department in Kansas. Then, in 1935, he started Cerophyl Laboratories to further his research and experimentation.

Even though Cerophyl has a fully equipped laboratory in Kansas City and another one at the Midland facility, Schnabel often conducted research in a basement laboratory in his own home. He was sometimes growing wheat under bright lights to examine early stages of growth.